How Gandhi inspired Methodist peacemakers

By David W. Scott

May 2020 | ATLANTA

The impact of one person lies behind much of the mission of 20th century Methodist peacemakers: Mohandas K. Gandhi. The Mahatma (or “great soul”), while neither Methodist nor Christian, nonetheless influenced Methodist missionaries in India, and through them, other mission leaders around the world.

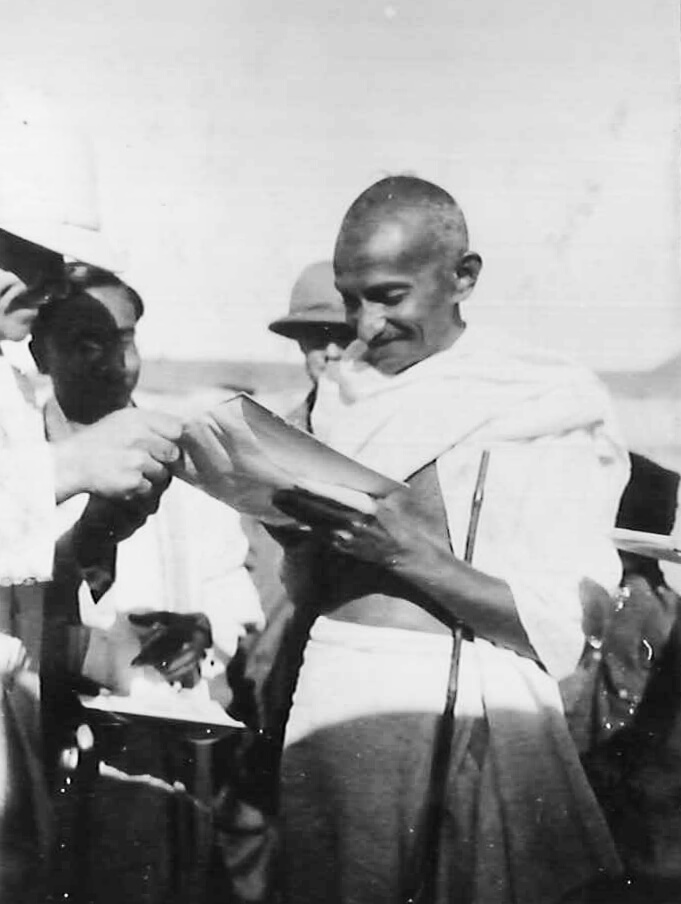

PHOTO: GENERAL COMMISSION ON ARCHIVES AND HISTORY

Gandhi was part of a broader movement that sought the end of British colonial rule of India, but his unique contribution to that movement was the philosophy of satyagraha, or “soul force,” usually referred to as nonviolent resistance. This philosophy proved appealing to Methodist missionaries who met, corresponded, and worked with Gandhi between his return to India in 1914 and his death in 1948. Satyagraha shaped Methodist involvement in peacemaking, nonviolence, anti-colonialism, civil rights in the United States and a host of other issues.

E. Stanley and Mabel (Lossing) Jones

Perhaps the Methodist missionary who was closest to Gandhi was the Rev. E. Stanley Jones. Given Jones’ interest in interreligious dialogue and contextualizing Christianity into India, it is perhaps not surprising that Jones would have found Gandhi an intriguing figure. The two, however, became quite close, and Jones wrote two of the earliest books on Gandhi, “Gandhi: Portrayal of a Friend” and “Mahatma Gandhi: An Interpretation,” both first published in the U.S. by the Methodist-affiliated Abingdon Press. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. later read Jones’ writings as part of his introduction to Gandhi.

Jones also borrowed from Gandhi’s model of ashrams, or spiritual retreats, as nuclei for religious and social reform. Jones founded his own Christian ashram in Sat Tal, India, in 1930 and later expanded that beginning into an international Christian ashram movement. These ashrams were focused, in part, on promoting peace across religious and racial divides.

PHOTO: GENERAL COMMISSION ON ARCHIVES AND HISTORY

Jones went on to promote international peace between Japan and China in the 1930s, between Japan and the United States before World War II, in Burma and Korea in the late 40s and 50s, and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the 1960s. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1963.

Mabel Jones, E. Stanley’s wife, was also a friend and correspondent of Gandhi’s. She and Gandhi wrote regularly about education, a significant interest of Gandhi’s and the focus of Mabel’s missionary work. The value that Gandhi placed on all people fit with Mabel Jones’ noted egalitarian approach to people of all races, nationalities, social classes and genders.

Eunice Jones Mathews and James K. Mathews

Gandhi was also a significant influence on Mabel and E. Stanley Jones’ daughter, Eunice, and the missionary she married, the Rev. James K. Mathews. Eunice Jones served as a literary assistant and editor for 25 books of her father’s and nine of her husband’s, helping share their Gandhi-influenced

understandings of mission, Methodism and world events. James Mathews admitted in his autobiography that “these very memoirs should be titled, ‘We Did It Together.’” Throughout her life, Eunice maintained relationships with Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and other world leaders and was remembered at her passing as a consistent advocate for peace.

James Mathews came to India in 1938. He traveled to E. Stanley Jones’ Sal Tal Ashram, where he met the Jones family and was introduced to Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence. Jones later wrote his dissertation at Columbia University about satyagraha, which was eventually published as “The Matchless Weapon: Satyagraha” in 1989. James Mathews maintained life-long friendships with Gandhi’s grandsons Raj Mohan Gandhi and Arun Gandhi.

PHOTO: MIKE DUBOSE, UMNews

Throughout his work as an executive at Global Ministries and a bishop of the church, James Mathews was significantly involved in the civil rights movement, another product of Gandhi’s influence on him. He participated in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He and fellow bishop, Charles Golden, an African American, were barred from integrating an all-white church in Jackson, Mississippi, on Easter Sunday, 1964. In 1978, Mathews participated in “The Longest Walk” on behalf of Native Americans.

Ralph T. Templin

The connection between Gandhian nonviolence, peacemaking and civil rights is also exemplified in the life of Ralph T. Templin. Templin and his wife, Lila, went to India as educational missionaries in 1925. Like the Joneses and Mathews, Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence had a significant impact on Templin. Templin wrote a never-published manuscript on Gandhi, and his major published book, “Democracy and Nonviolence: The Role of the Individual in World Crisis,” clearly shows Gandhi’s influence.

Templin was expelled from India in 1940 because of his refusal to take an oath to the British colonial government, an expression of his sympathy with Gandhi and other Indian nationalists. Back in the United States, Templin helped found the Harlem Ashram in New York City. The ashram’s interracial community included many associated with the pacifist and civil rights movements. With others in these networks, Templin helped form Peacemakers, a pacifist organization, in 1948. His connection to Puerto Ricans in Harlem also inspired support for Puerto Rican independence.

Templin served as the head of the nonviolent School of Living in Suffern, New York. Templin later moved to Ohio, where, in 1948, he became the first white faculty member of the historically black Central State University, teaching sociology there. In 1954, Templin transferred his ministerial credentials to the Lexington Conference of the all-black Central Jurisdiction, the first white clergyperson to do so.

Walter Brooks and Mary (Rosengrant) Foley

The Rev. Walter Brooks Foley and Mary Foley arrived in India as missionaries the year after the Templins. Like their colleagues, they too met Gandhi and became involved in the Indian independence movement. In 1931, they were expelled from India because of their connections to that movement.

They returned to the United States for four years before going out again as missionaries to the Philippines. There, they continued to practice Gandhian principles of nonviolence by working for peace

and against American colonialism in the Philippines and Japanese aggression in China. In part because of their resistance to Japanese militarism, they were imprisoned during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. In prison, they continued to serve others by providing food and education. Tragically, Walter was killed, and Mary maimed by a Japanese bomb, four days after being liberated from the Japanese prison camp.

The Foley’s story has an afterword that shows the enduring impact of Gandhi on Methodist mission, even beyond those missionaries who knew him personally. The Foley’s daughter, Frances-Helen, who was two when the family left India, was one of the first Crusade Scholars after World War II. Later, Frances-Helen Foley Guest became one of the first female pastors in the Florida Annual Conference and an advocate for racial and gender equality.

A Broader Legacy

The influence of Gandhi on other Methodist peacemakers who did not know him personally, but knew those who did, is visible elsewhere. As a young adult, the Civil Rights leader James Lawson was a Methodist missionary to India for three years, after Gandhi’s death. Nonetheless, Lawson was influenced by Gandhi and deeply committed to Gandhian principles of nonviolent resistance. Martin Luther King Jr. called Lawson “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.”

The Rev. Dr. Richard Deats served as a missionary in the Philippines, not India. But E. Stanley Jones and others influenced by Gandhi were among his teachers and friends, and through them, Deats was introduced to Gandhi’s thought. He became heavily involved in the pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation and was another Methodist missionary (following Jones and Mathews) who wrote a biography of Gandhi, “Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Liberator.”

In that book, Deats wrote, “In my peace ministry spanning the last half of the twentieth century, I have continued to drink deeply from the well of Gandhi’s life and thought.” What was true for Richard Deats was true for The United Methodist Church as a whole.

Dr. David W. Scott is a consultant and mission theologian with Global Ministries.